Brothers, Fathers, Friends and Lovers

Flesh Tones

Yannos is taking us with his boat to Goat Island, an islet off the southern tip of the island where I’ve been staying this month. I can’t think of why the presence of goats on any island in the Aegean would be noteworthy enough to name it after them, but he tells me that even when there were people on the island the goats greatly outnumbered them. “It always belonged more to the goats.”

As we approach the island I can see the rock rising steeply at the shore, a wall of limestone crowned by barbed quills of stone that pierce the sky. The face of the cliff is scored with wedges of iron ore that bleed into the white rock. I had expected a gentler landscape, mostly because of the goats, but then I think, I haven’t yet seen the headland on the other side of the cliff.

Yannos eases us into a small cove ringed by a thin crescent of beach. Shielded by arms of rock that embrace the cove on both sides, the water here is calm and impossibly translucent, colored only by the rocks and grass deep at the bed of the sea. There are coves like this on other islands in the Aegean; most are known only to locals and only accessible by boat. They have names like Swimming Pool or Hideaway, if they have a name at all.

The others have already stripped to their bathing suits. I take off my shirt. It’s a long-sleeved madras button-down that my friend Nina gave me before I left, a good-luck token, she said, in anticipation of the island romance she was hoping I would have.

“My dear!” Margaret says. “You’re as pale as Madame X.”

I don’t catch the reference at first. My mind wanders to a femme fatale in a Basil Rathbone film or a role Greta Garbo may have played. You couldn’t always tell with old black-and-white movies, all the women looked pale back then.

“The Sargent painting,” she says. “You’ve seen it of course.” It wasn’t an expectation as much as the certainty of a fact of life.

I recall the painting, the portrait of a beautiful woman with a ghostly lavender pallor, dressed in a low-cut black evening gown.

“But not as blue, I hope,” I say.

“Now that you’re here, you need to get some color,” Yannos tells me. He says it in the same way he talks about my reserve, as if to say that my paleness, like my introversion, were a sign of a deliberate retreat into solitude, as if I had chosen to be quiet and pale.

“The only colors I get are pink, red and first-degree burn,” I tell Yannos. Margaret, who despite her ash-blond hair has acquired a light tan during her long stay on the island this summer, smiles, but Yannos just grunts and gives me the look a parent gives a willful child who pretends to be sick on a school day.

He has the deep tan of an islander who spends his day in the fields or at sea. I envy his insouciance in the sun. I can burn even with sunblock, so I am conscious of my exposure to the sun and always in search of shade. For me the sun is like a reckless lover with bad habits, whose seductive enthusiasm all too easily prevents you from seeing the harm that will come to you if you stay too long in his presence.

We dive off the boat for a swim. Margaret heads off to explore a low-slung cave at the entrance to the cove, Telis to snorkel for sea urchins. Yannos heads for the beach in the high breaststroke of swimmers who wear their sunglasses in the water.

Once ashore, he flings himself onto the back, rolling onto his back to lie in the sand, head pointed to the sky and arms thrown back. He looks as if he’s on his bed waiting for his lover to come.

I think of how Yannos would have looked in his youth. It is easy to do this, because there is still much of the young man in him.

I am certain he was an attractive young man. His body would have been thin and hard, and burnished by the sun. Like now, his eyes, a brilliant silver-green, would have had the crystalline quality of the water in the cove. He would have lacked the great physical beauty of the leading man; instead he would have been the smarter accomplice, the witty but sexy roommate, a wiry, sensual man with a story on his tongue and a talent for winning people over.

He would have been the kind of young man that men from the North would find in villages in the Mediterranean and the Maghreb and would photograph, one of the nameless Antinooi whose images would find their way into the homes of equally anonymous private collectors. He would have been the kind of young man that Sargent, too, might have painted.

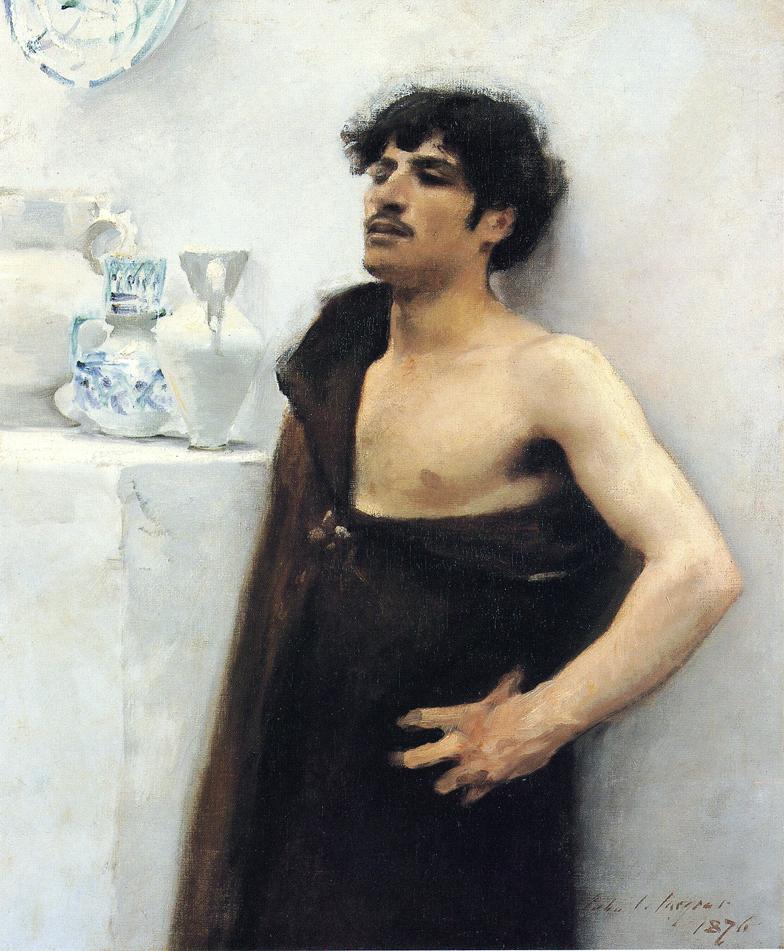

I think of another Sargent painting, of the kind he painted solely for his own pleasure. A handsome young man with an unruly mop of black curly hair lounges against the whitewashed wall of a village house. His cast of features and color speak of the Mediterranean, as do the white and powder-blue ewers that stand on a ledge to his side. He’s thrown a maroon cloak over his naked body, hastily it seems, leaving one shoulder exposed. It’s looks less like a proper piece of clothing than a coverlet, grabbed perhaps from the bed where he and the painter have just made love.

There is something defiant in the man’s sensuality, something rapacious in his seduction: the way his pelvis is thrust forward and the head cocked high, something about the hand that looks like a claw, the imperial tunic. It’s as if Ganymede had taken on the role of Zeus.

Yet this is no painting of a summer lover, as I thought when I first saw it, but rather a portrait of his valet, Nicola d’Inverno, who was roughly the painter’s age. Nicola appears in a few other paintings and sketches during the 20 or so years they were together. They are all intimate works. One is of him reading on a bed. In another he is playing chess on the lawn with the painter’s niece. Yet another is a sketch of a reclining nude. Though the paintings are few in number, they suffice to give a loving portrait of a beautiful young man as he becomes a beautiful older man.

It is hard not to believe that they were not lovers, though critics say there is no evidence to confirm their relationship, or disprove it, for that matter. Sargent was a very private man. Klistos, as Yannos would say.

This was the word Yannos used when he remarked on my own reserve in the first days of getting to know each other. It’s same word that is used for closed shops, shut doors, and the tightness of small narrow spaces. I thought it was a rather personal thing to say to someone you don’t know very well. But Yannos says that’s part of my problem. “How do you become personal with someone if you never say anything personal in the first place?”

For him, it’s a mere matter of will, and perhaps not even that. You go out in the sun and tan. You go out for a boat ride and tell stories and reveal yourself. I tell him I don’t have it in me. I lack the pigment for the one and the disposition and character for the other. I tell him I am happy in my skin. He thinks I’m being stubborn, as if my reserve were deliberate or artifice, like the lavender blush powder Madame Gautreau applied so liberally to her skin before her sitting with Sargent.

I’m never sure at first when someone tells me that I’m quiet—as if this were news to me—whether it’s intended as criticism or an encouragement to open up or something else I haven’t figured out. I do know that it’s almost never positive.

Matthew once told me—it was shortly after I moved in with him—that he knew I was right for him because we could be together in the same room without the pressure to talk or entertain each other. “I remember the first time you stayed over, how you sat in the living room quietly reading your book while I was working at the desk. I’d never done that before, just be with someone, and it was wonderful.” But by the end of the relationship this same introversion, this same reserve, was a source of discord between us. It was now apathy. “You just sit there absorbed in what you’re reading or writing,” he complained, “absorbed in your own world.” But I don’t blame him.

I watch Yannos from the boat, his body a rich brown Y on the white sand, and I think of the portrait of Nicola in Capri, and the outline of the valet’s body against the white wall. Yannos looks like the kind of man Nicola might have grown into, years after Sargent stopped painting him, and Nicola the young man that Yannos might have been.

Once we’re all back on the boat, Margaret digs into her canvas bag and withdraws a stack of three stainless steel canisters, the kind you see in dim sum parlors. “Just a little something to keep us till dinner,” she says, in her gentle, patrician voice, all Radcliffe and summer breezes. The canisters hold oil-cured olives and cherry tomatoes and chick-pea fritters. She takes out some barley rusks and dips them in the sea to soften, and then tops them with the tangy local farmer cheese.

“Manolis?” Telis asks and Margaret nods. They all know, except me, the new arrival, where to get the best cheese, as they do the location of coves like this and the etiquette of boating parties. I wish I had thought to bring something, too. I tell myself I will treat the others to coffee when we get back to port in the afternoon.

I put my shirt on. Although it hasn’t yet brought me the kind of luck Nina was thinking of when she gave it to me, I am lucky to have met Yannos. I know, however, I will disappoint him in his project to change me. He will know how very fond I am of him and how much I enjoy being with him. I will slowly share my stories and then my dreams and fears with him. But my reserve and need for solitude will not change. It is part of who I am, as much as Madame Gautreau’s ambition and unpaintable beauty, and Nicola’s — and Yannos’ — sensuality are a part of them. It is how I would be painted.

As we eat our simple lunch, a meal not all that different from what the two young lovers might have had during their stay in Capri, I ask Margaret if she knows what happened to Nicola. He would have been in his late 40’s when he left Sargent’s service. A pension, perhaps, and a cottage where Sargent would come and visit?

“Oh, nothing like that,” she says. “Sargent dismissed him. Some brawl he got into with another servant at a hotel they were staying at.”

I’m disappointed by this ending, the way it turns Nicola back into the valet. But then I think, no one really knows what went on in the hotel. There’s room for another story.

-/-

Image: Young Man in Reverie, John Singer Sargent, 1876

I started to research this because my great great aunt Sally worked as Singer Sargent’s housekeeper in Chelsea and was married to Nicola D’Inverno. They had no children and I know nothing about their relationship – except that, as godmother to many of her sister’s children (including my grandmother) she chose many of their names, calling one boy Nicola after her husband. The row you refer to took place in America and ND’I never returned to Sally or to England but set up in business as a photographer. He had had a studio in the Chelsea house – possibly to take reference shots for the photographer? – we have a splendid photo of Aunt Sally. When JSS died, N’I sold an interview to a Boston evening newspaper. His memories of JSS as an open-handed employer who paid for his gym membership and shelled out to cover his gambling debts offer a small insight.

LikeLike

What a fascinating story! Thank you so much for sharing it.

LikeLike

If you were an extrovert, do you think you’d feel the need to write as beautifully as you do?

LikeLike

What a lovely thing to say, thank you!

LikeLike