Memory

Secrets of the Thicket

The woods lay at the end of a dead-end street. The asphalt ended somewhat awkwardly, unevenly and without a curb, as if the builders had suddenly changed their mind and abandoned construction. A tiny creek separated the end of the road from the woods, easily hurdled, but for a ten-year old who was always looking for an excuse to get away from his pesky brother and forever quarreling parents, it was an important demarcation. The creek marked the boundary between their world and mine.

I loved the woods, its cool darkness, the musky scent of the earth, the softness of the moss. Though I rarely saw an animal, I knew the woods were very much alive. I could hear it in the sounds of twigs creaking, leaves rustling, something scurrying past me, I could hear in the buzzing and hooting and squawking of birds and insects. But there was something else I felt there, a kind of indefinable presence in the woods of some, what, spirit? I couldn’t have known, then, of course, but the Romans would have called it the genius of the woods, the instantiation of the divine in a particular place or person.

The woods didn’t extend very far. I could walk around the perimeter in a half an hour. And I quickly came to learn every path. Sometimes I played there with other kids but not that often. I preferred to be there on my own. It was a refuge of sorts. It was my place, or at least a place I had made mine. There was a big rambling thicket, almost tall enough for me to stand in, and it had grown in such a way as to form three little interconnected enclosures. I cleared away the undergrowth, rocks and dead leaves, and made a three-room studio out of it. I called it playing fort but that it was really playing house by another name.

To get to my fort, I had to slip by the twin dangers of Sean McCann and Billy van Houten (or to be precise Billy’s German Shepherd, Raya), whose houses flanked the entrance to the woods. Both had attacked me in the past and I was sure they would do it again if they had the chance. Maybe they were just born mean, or were made to become that way, but the ten-year-old in me needed to have a better, more immediate reason than that. Raya had attacked me one day when I had gone to call for Billy. I was standing on a little hill at the edge of their property, calling out his name, when the dog rushed up the hill and started nipping at my calf. I was convinced that the little hill was where they had buried Raya’s puppies.

Kids want the world to make sense, even if the sense it makes needs magic to work. They want a reason, an explanation. Maybe that’s why they so easily believe they’re at fault when their parents separate. To suspend belief and tolerate uncertainty is something we acquire only as we grow older, and only through a process of watchful self-discipline.

The quantum ethics that mark the entangled state of everyday life is both the prerogative and obligation of adulthood. We learn, or should learn, that at times there’s no right or wrong or, rather, something can be right and wrong at the same time. We come to accept that he loves me and he loves me not. The fine line between the two, or between courage and foolhardiness, or altruism and self-deprecation, is no line. It’s more like the elusive, barely discernible boundary between the whites of two raw eggs on a saucer.

If, as Geertz said, “man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun,” children weave theirs with borrowed threads. But these eventually fray. The last of the personae in the fables of my childhood that I was to abandon was that of my guardian angel. Maybe I clung onto him—yes, my angel was definitely a he—because I didn’t have an older brother who would protect me and teach me things. My guardian angel didn’t do much. It wasn’t a voice of conscience, like in those silly cartoons in which a little red devil hovers about one ear and an angel in white about the other. No, mine was silent, but I felt that if I were ever in real spiritual danger, he would intercede.

The closest I came to having a real guardian angel was Ricky Morgan. He lived next door to us in the city. Though he was already in high school, he had taken a liking to me. I still don’t know why. Maybe he was missing a little brother. But whatever the reason, he watched out for me on the block and made sure nobody would pick on me.

I remember playing “King of the Stoop” with him. This was the game where Ricky would sit in the middle of our brownstone’s stoop and I’d try to scale the steps and get past him to the top to claim title to the stoop. Without fail, of course, Ricky would grab me as I tried to sidestep him, and he’d wrap his arms around me and squeeze me until I’d say uncle. I resisted as long as I could. I didn’t want to give up. I loved being trapped in his arms, his wonderful protecting arms. I remember my crotch would swell, though I didn’t know what that meant, and I looked up at his face, at his broad cheekbones that seemed to me like mountain boulders, and I wished I could grow smaller and smaller until I could rest, like a baby eagle, sheltered within the indentation below his cheeks.

When I was eighteen I hitchhiked to San Francisco from New York. I might never have made it to California and would have probably returned home a few weeks later once the money I had with me had run out, had I not been lucky enough to catch a ride from a guy that was going straight on to the coast. The 1960s pink Cadillac he was driving broke down in Indiana, and he just bought another used car. (This was one of the few times in my life I was ever tempted to believe in fate).

I stayed in San Francisco for a year. I came out in the city, but I never once stepped foot in a bar. Instead I went to the parks. To the woods. I must have been desirable or just plain young, or maybe it was San Francisco and before AIDS, but it was so easy to have sex. I would just hang out along one of the paths in Lincoln Park and sooner or later, but usually sooner, an attractive guy would come by and we’d hook up.

My straight friends (and indeed, some of my gay friends) couldn’t understand why I’d want to have sex with a stranger in a park, with all the risks that doing so entailed. Like running into a petty thief or sadist or some sick twisted, sexually messed up punk looking to vent his rage on some gay guy. Or even worse. I told them I just could just as easily run into them in a bar.

The sex I had in the park was different from what happened in a guy’s bedroom. It was hungrier, more rushed. And admittedly more uncomfortable. Although there’s an erotic edge to being undressed in the woods, relinquishing the trappings of culture in an environment (relatively) untouched by culture, the woods are fully of prickly, abrasive, and jagged surfaces. Cranach’s nymph of the spring may be lying blissfully content on the forest floor, naked save for a flimsy, near transparent slip, but that’s an allegory. Flesh was not made to rub against bark and pebbles.

I was lucky. I never got hurt. There were a few obnoxious, arrogant, selfish or pathetically needy men among the (larger in number) decent guys I met. Maybe I had a guardian angel. In fact, the Christian tradition of guardian angels, like many of the more populist traditions of the early Church, was appropriated from Roman religious practices, specifically, from the genii. There were genii of the forests, too, of course, spirits that dwelled in remote woods and who could, if needed, guide a man in the hour of need. Maybe there was a forest spirit in those places. A faun.

If there had been, he would look like one of photographer Caroline May’s subjects. For years she’s been taking photographs of hustlers, sometimes in parks and–in a recent series of photographs exhibited at the Apartment–in the woods.

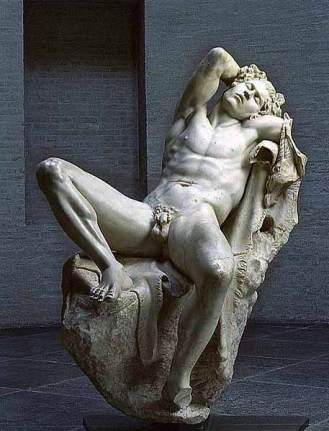

May’s faun wears nothing but a beltless forest-green pair of combat pants, revealing a ripped torso, flaring lats and a geometric tattoo on his muscular shoulder. He wears his pants low, below his hips. In one photograph, we see the beginning of the furrow between the cheeks of his ass; a small triangle of downy hair rises up his back from the crack like some small reminder of his caprine ancestors. In another, this time shot from the side, half of the crescent of his buttocks is revealed. This is a very sexual faun, “well-practised in the secrets of the thickets”, as Nonnus had said of another faun in his Dionysica. More teasingly so and less lustful than the Barberini faun (who seems so awash in pleasure as to be utterly oblivious to his surroundings), but definitely sexual.

May’s faun is at home in the woods. He is the spirit of the place, the genius of the woods, It’s his playground. You see it in then way he lounges against the tress, his mouth slightly open, his head cocked to the side as if he had just heard someone approaching. Maybe he’s not looking for sex, just looking out for the others. I’d like to think so.

-/-

Image from Caroline May’s exhibition at “The Apartment”

what a wicked christian you are, after all [that education]! 😉

to connect guardian angels to genii silvani!

[for which we other heathen are grateful :-)]

LikeLike

Ah, my poet friend, what a gem of a comment you’ve provided! Thank you for this (and the one you wrote for Books and Boots). Looking forward to our Saturday tea/coffee. S./

LikeLike