Sexuality and Identity

Taking Sides

I only noticed his hands because he was writing. The way we used to write but don’t so much now: with a pen in hand.

I would have taken note of him anyway, as he sat there alone at one of the dollhouse-like tables that were the café owner’s begrudging concession to the solo patron. There was something that set him apart, and it wasn’t just the leather-bound writer’s notebook he had beside him. Perhaps it was the snug taqiyah that he wore over his shaved head or the disciplined way this spare young man was sitting, back erect and slightly bent at the waist as he quietly wrote. Both gave him the air of a monk.

He wrote with his left hand. This was enough to set alight within me a feeling of solidarity with the young scribe, the recognition that we shared something. This something wasn’t particularly important. If it were a conversation starter it would exhaust itself in its utterance. But it was a solidarity to be experienced—or savored—nonetheless, a gentle and pleasurable inflammation of memory, triggered by the remembrance of the small and inconsequential wounds that our left-handedness occasioned, things like ink-smudged hands and scraped knuckles in the kitchen and badly wrapped Christmas presents.

Handedness is not something you ordinarily pay attention to, much less mark in memory. If we left-handers represent about 10% of the population, I must have a couple dozen left-handed friends, colleagues and acquaintances right now. But I can remember only four at the moment: two good friends, a brother and a legendary spinning instructor, and I only remember the last because of a nameday gift I wanted to buy him. Actually I did buy him the gift—it was a long-handled briki pot to make Greek coffee in (with the spout facing right)—but I was embarrassed to give it to him. As I said, it’s not the kind of thing we make a big deal out of.

I knew nothing about the young man other than that he was left-handed. We likely had very little else in common, but the handedness sufficed. It felt like running into a countryman on a foreign beach or discovering another gay man among the wedding guests at your table. Immediately a store of shared experiences becomes available, and these tales need no translation or exegesis. We simply know.

But it was a paltry inventory we had in common. It was nothing like the immense treasuries of song and food and language that those two compatriots on the beach will draw upon, or the sweat-drenched dreams and heavy memories two veterans might share. No, ours is a litany of petty inconveniences, easily suffered and often taken for granted. (Luckily few of us have to contend with the greater dangers of circular saws and power drills.) And if it is a stigma, it is one that is revealed only in a limited set of actions and only discernible to the agent itself. Only the hand that cuts knows the inconvenience of a pair of scissors whose blades are forced apart as one presses down.

Sometimes we are not even aware of our own disadvantage. Take bread. I cut a loaf in uneven slices that get thicker as I reach the bottom of the loaf; a few breakfasts later and the cut end of the loaf looks like an overhanging cliff. For the longest time I was certain that this had to do with poor knife skills and the sponginess and springiness of bread itself. This is the way bread is cut, I said. I now realize a bread knife has only one serrated edge, and mine was always on the ‘wrong’ side.

Sides. There are just so many sides on a device where one can put the serrated edge, the on/off button, the shutter release, the volume control.

It’s about torque, too. We left-handers are disadvantaged not by social convention, policy and prejudice but by the things our world builds and the tools we use. We struggle not with directives about whom we can marry or how much we pay in taxes, where we can live or conventions on who gets hired or promoted, but instead with how things turn. Staircases, dials, knobs, latches, clasps—they all move in just one way in order to do what they’re designed to do. Ours is a discrimination predicated on physics.We are disadvantaged not by law but by tools: retractable tape measures and swivel peelers, bread knives and electric saws.

We left-handers know the asymmetry of our built world much better than our right-handed counterparts do. We are aware more than many others of the countless design decisions that require the use of one over the other hand. In many cases we unconsciously capitulate, using our non-dominant hand to open store doors and cans of stewed tomatoes (the latter much more clumsily than the former, I must admit).

But it is writing most of all that is the litmus test of our identity. In fact, most would define handedness only in terms of what hand we use to write. It is not only harder for us but also different. It’s not just the ink smudges. Given the angle and direction of our script, when we write we push the pen into the paper, rather than drag the pen along. Our writing is an act of subtle penetration (which explains why we run out of ink faster than they do).

Here are some other things we find harder to do:

Sharpening a pencil and using a three-ring binder. Ladling soup, opening a can, and scooping ice cream. Making Greek coffee. Throwing a boomerang. Digging change out of our jeans pocket. Freeing our pride from boxer shorts. Picking up a bowling ball, arm wrestling, and opening locks.

It’s all about sides and direction. Kissing someone of the cheek. Raising an arm to be helped into our coat. Shaking hands.

—

Luckily we no longer need to ask the question “Is it okay to be left handed?” But an intriguing video produced by Beyond Blue, an Australian organization dedicated to preventing depression and improving the quality of life for those affected by it, uses left-handedness to answer just that question. Or put otherwise, why should I be made to feel like crap for just being who I am?” (The point of the video being, of course, that there is no reason)

–

The video starts with a scene of a teenager having breakfast in a sunlit suburban kitchen. Something on TV has made him smile. And he has the most infectious, winning smile. He’s a good kid, that’s clear in an instant. [Note, 3/17/2016: the original video is no longer available online; this post features a shorter version that omits the first scenes at home]

We see his mother in the foreground watching her son. There’s a sharpness in a voice when she barks to him, “Hoy, what are you doing?” What exactly is he doing, I wondered. Laughing at an inappropriate joke on the TV? The next scene is in the bathroom, where he and his younger brother are brushing their teeth. We hear the father’s voice from down the hall ask, “Are you ready yet?” The elder brother quickly switches the toothbrush from one hand to another and continues brushing his teeth. Now I know.

We follow the teenager through a day at school, He’s called a freak and threatened because of his differentness by school bullies (and in all places in the power-tool laden shop class!). He’s made to feel incompetent by his teachers as he tries, without much success, to accommodate to the (hand-)dominant culture and write with his right. At dinner later that afternoon, as he raises his glass with his left hand, his father asks “why can’t you just be normal?”

The video depicts the arbitrariness of discrimination and the struggle of every young person who, for whatever reason, innate or by choice, is different. Aided by the absurdity (in our day at least) of its very premise—the stigmatization of left-handers—the video is able in just a few scenes to depict the injustice of the (essentially futile) effort to “pass” , to “fit in” when one’s very body or sense of self calls out to express itself differently.

I stopped taking notes—yes, I was writing, too, a fellow scribe and a left-handed one, too!—and looked up. The young writer was gone. I suddenly felt the need to remind myself how it feels to use my right—my weak, my subordinate, however you want to call it, my non-dominant—hand. I turned around the large bulky cup of coffee I had ordered, and grasping it in my right hand, raised it to my lips. I didn’t spill anything, of course, but it didn’t feel comfortable. It was like pretending to like girls in high school. I could do it, but it wasn’t me. It was then that I noticed the café’s logo embossed on the cup. It is was the first time I had seen it.

-/-

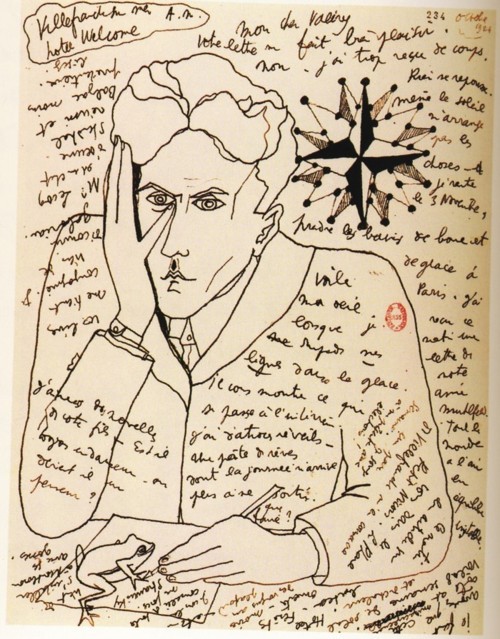

Image: Self-portrait by Cocteau, 1924

My brother is a lefty, and although I don’t think he received the taunts that the young man in the video did (certainly not from home), I am now left to wonder. I’m sending him a link to this blog post as a reminder that I’m thinking about him and his feelings. Thank you for your wonderful writing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You bring back for me the days before I had learned to type — when the bottom of my left hand was always smeared with blue. Now it is smart phones that are difficult, especially taking pictures with them. Can you click deftly on the right of your screen? I can’t. I’m still inadvertently photographing part of my palm. By the way, the quality of your writing is impressive. I’m glad I stumbled upon your site. 🙂

LikeLike

Wow, I do the same thing with my phone camera! And I thought I was just a clumsy photographer 🙂 Thanks for the kind words about the blog. I’m enjoying reading yours (the practice one, too). I hope you do write someday about your experience as a woman a law school in the 50s, as you said you might. I’m sure you’d tell an intriguing story. S./

LikeLike

I meant I went to law school in MY fifties. There were lots of women there then, much much younger than I was! And I probably will get around to writing about that, sooner or later; you run out of material quickly when you try to blog every day, as I have been doing. (How long I can keep it up, I don’t know.) In the 1950s, which is what I think you were asking about, you’re right that there were no more than one or two women per class. They weren’t me. I was a flibbertigibbet who believed men were what life was all about, and majored in literature because I liked to read novels and wasn’t interested in much else. Thanks for reading my blog, though; I didn’t know you were there. (You leave no footprints!) 🙂

LikeLike

I just found your blog today, it’s great. I grew up being told to write with my right hand, put the fork in my left, etc, and didn’t think much of it until later in school when, by chance, my two best friends were left-handed. I tried it and it was fine. These days, I type. I told my children they could use either hand and, being very young, they took me literally and swap hands whenever they feel like it. If you give me a pen, habit dictates I’ll use my right (probably), but it still feels better with my left — whereas with a computer mouse I can barely function at all w/ my right hand. (Gillian, the trad keyboard uses the left hand more than the right, in English — also no ink smudges.)

LikeLike

Thanks for the nice feedback! You’re right about the keyboard — in a typical text slightly more keystrokes will be found on the left hand side of the keyboard. Except when I type. The key I use the most is on the upper-right: the backspace key 🙂

LikeLike

Great video campaign, love the analogy – thanks for sharing it!

LikeLike

Your writing is lovely, offering at once a gentle yet powerful glimpse into the heart of a young gay man. I clicked over to read what had been Freshly Pressed, and stayed for more. Thought I’d comment on this one, as I am also left-handed.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for commenting and the lovely things you say about the text.

LikeLike

This was such an interesting article. It made me rethink about my left handed daughter her left handed partner and young left handed grandson. What I found fascinating with my daughter was that she worked in retail with computers. A good 80 percent of her colleagues were left handed. Why?

LikeLike

I just love the way you look at details and make us see a much bigger picture.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your kind comment!

LikeLike